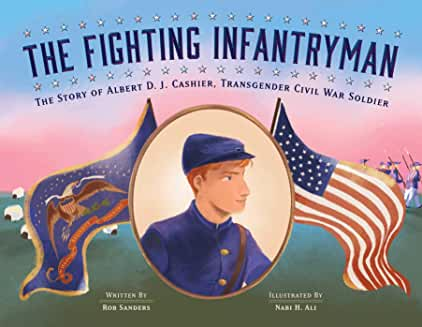

The Fighting Infantryman: The Story of Albert D.J. Cashier, Transgender Civil War Soldier (2020), written by Rob Sanders and illustrated by Nabi H. Ali, provides young audiences access to a fascinating queer historical figure. Like most picture book biographies, this one begins when the protagonist is a child. As a result, instead of meeting Albert D.J. Cashier on the first page of the book, readers meet Jennie Hodgers as she collects shells on a beach in Ireland.

In subsequent pages, the child grows into a teen. Throughout her early years, Jennie often wears boy clothes. Sanders suggests this is because wearing pants is easier when tending sheep, and, later, while sailing to America with her stepfather, because it is “more practical – and safer – that way.”

Once in the US, a young Jennie begins using the name Albert D.J. Cashier. Sanders doesn’t speculate as to why this is.

When the Civil War begins, Albert decides to enlist. He passes his physical and begins training. Several pages of the book depict Albert working alongside other soldiers.

After the war, Albert continues to live as a man. He collects a military pension and supports himself farming.

Throughout the text, Sanders describes Albert as a true patriot who grows into his identity alongside a country struggling to grow into its identity.

Albert lives peacefully after the war, until suffering an injury when he is in his sixties. At this point, his doctor and employer learn that Albert “wasn’t born a man.” However, they agreed not to tell anyone.

Sadly, as Albert’s health worsens and more medical professionals examine him, Albert is increasingly vulnerable. Eventually, a nurse tells a reporter that he is not a man, which eventually leads to his participation in the Civil War being questioned as well as his military pension being compromised. At one hospital, Albert is even forced to wear dresses. However, even as he experiences this awful abuse by the medical institution, the soldiers he fought with work to have his military pension continued and his gender identity respected. The government finally agrees.

Upon his death, the men Albert served with ensure he has a full military funeral.

In back matter, Sanders acknowledges the difficulty of identifying Albert’s motivation. He writes: “We don’t know for certain why Albert D.J. Cashier lived his life as a man. Maybe doing so was more comfortable, more convenient, or safer. Maybe Albert lived as a man because it provided him with more opportunities and choices in life. But it’s likely that Albert was transgender and identified as a man.”

I like much of this book very much. I do, however, have concerns about the text’s opening. First, I don’t know that we need an image of Albert as a young girl collecting seashells. I don’t know if we need to begin with the deadname of this man who spent fifty+ years living as a man and using the name Albert. Additionally, although in back matter Sanders notes that we don’t have access to Albert’s motivation, he attributes practical motives to Albert’s early decision to wear of masculine attire. For instance, at the text’s opening, Sanders notes that wearing boy clothes made it easier to tend sheep and, later, that it was safer to dress as a boy while traveling to America. These representations move beyond statements of fact to interpreting and implying motive.

Overall, I like this book. My critique is meant to elucidate the real challenges of representing transgender identity in picture book biographies, especially those of historical characters whose language to describe gender was very limited, and whose nuanced motivations and personal identifications are likely inaccessible to contemporary biographers.

Leave a comment